|

|

||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

1819 |

The second child of Marianne and Friedrich Wieck, a daughter, is born in Leipzig (Leipsic *) on September 13 and is given the names Clara Josephine. The couple’s firstborn, daughter Adelheid, died as a baby the year before. The father has studied theology but now owns a store selling pianos and musical supplies, and he is much in demand as a piano teacher. The mother, née Tromlitz, was his first student, has become an excellent pianist and is a great help in the family business. For quite some time now she has had problems with her brusque, testy and irascible husband. * The cities under the names given here or in brackets and marked in blue are underlined on the contemporary map to the right. |

|

1824 |

Clara is four years old and has three little brothers by now. The parents decide to separate; according to the law then in force, the father retains sole custody of the children. Magnanimously, he allows the mother to take the baby along to her parents in Plauen near Berlin and he lets Clara stay with her for another few months, until the child’s fifth birthday in September. |

|

1825 |

The parents’ divorce decree is issued in January; in August, Marianne marries the piano teacher Adolph Bargiel who is 13 years her senior. She rents a flat near Leipzig in order to be close to her children. Her three little sons, just one, two and four years old, live in a boarding house. Clara now lives with her father. She hardly speaks at all and passes for “slow” but she likes to play the piano by ear, little melodies that are correct right away. Father Friedrich writes into Clara’s diary that he also had language problems as a little boy. He hopes to realize, with her, all his ambitions as a teacher and to develop her musical talent into a great career. He is strict and demanding in that: starting with this, her fifth year, she has a daily piano lesson of one hour and must practice for two hours every day. The father is a severe master and does not hold back on criticism. The little girl gets through all that because of her love of music. She soon develops (as she recalls) a “lyrical” tone at the piano that shall often be praised later. |

|

1826 |

Clara now attends a prestigious private school, albeit only during the first grade. Her schooling program then continues at home and is very intensive: a private teacher for languages, a cantor of St. Thomas’ Church for music theory, the conductor of the Leipzig opera house for composition, plus singing and violin lessons. The presumably psychogenic language block has disappeared. Wieck senior is forming Clara to become a star pianist along his precepts. |

|

1827 |

Clara’s youngest brother Victor dies, only two years old. |

|

1828 |

In the spring, Friedrich Wieck marries Clementine Fechner who is twenty years younger than her husband; the family moves into a more spacious house. One month after her ninth birthday, Clara plays the piano for the first time before an audience; with a girlfriend of hers, she performs a march for four hands by Friedrich Kalkbrenner. The presentation by the two students of Wieck’s is a great success according to Leipzig’s Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung. |

|

1829 |

Niccolò Paganini, the famous “devil’s fiddler”, gives a concert in Leipzig. At the occasion, Clara plays for him a composition of her own, one of four Polonaises [op. 1]*, then with her father a few days later once again, great honor, four-handed variations on a theme by Paganini, written by a friend from Dresden. * The numbering of Clara Wieck-Schumann’s compositions is that of the Thematic Index of her works by Paul-August Koch (see below). The house of the Wiecks is becoming the meeting place of Leipzig’s society with an interest in music, and much of that is owed to the growing reputation of Clara, the little piano virtuoso. On December 23, the young law student Robert Schumann hears her play Carl Czerny’s Rondeau mignon four-handed with her father; he is much impressed with her talent. |

|

1830 |

The ambitious father Wieck seizes the favourable moment and travels with his daughter to Dresden to begin the next phase of her education. A loyal fan of hers is the physician at the King’s court Carl Gustav Carus who spreads the word in his wide circle of friends. She plays brilliantly as usual, does not show any signs of stage fright and appears not to be intimidated by the important names in the audience. The Wiecks return to Leipzig with a trunk full of presents. The next phase in Clara’s career as a concert pianist begins in November with a solo performance in the Gewandhaus in Leipzig. She presents some of her own works but also pieces by contemporary composers and receives the applause to which she is already accustomed. From that date on, Clara’s performances follow each other in fast succession. It is an exhausting, grueling life but the petite virtuoso is just as ambitious as her father and takes it all in stride. Robert Schumann’s mother asks Friedrich Wieck if her son could possibly make it as a pianist as he wanted to give up studying the law in Heidelberg. Wieck declares with grandiose gesture that he could bring him to become a great master of the piano in three years provided he could curb his overflowing imagination. Thereupon, Robert’s mother and his legal guardian release the money he has inherited from his deceased father, in order to finance piano lessons with Wieck. Robert rents two rooms in Wieck’s large house, plays the piano all day long charming some ladies with music by Chopin or with his own compositions. Clara is now close to twelve years old; he first treats her as the child she is but is slowly developing more tender feelings as his admiration grows for her mastery of the piano, for her art of improvisation and for her phenomenal memory for music. |

|

1831 |

In September, Friedrich Wieck takes his daughter on an extended concert tour through several German cities and finally to Paris. In Weimar, Clara plays in the house of the venerated Geheimrat Johann Wolfgang von Goethe whose praise is somewhat reserved in comparison to what he had written ten years earlier about the performance of the young Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy. Concert performances follow in Erfurt, Kassel (Cassel), Gotha, Frankfurt/Main (Frankfort) and Darmstadt. The voyage is arduous because of the long rides in uncomfortable public conveyances covering only about 60 to 80 km per day and because of the dirty lodgings that are often the subject of the father’s complaints in the diary they keep. It is severely cold this winter; in badly heated hotel rooms Clara can hardly practice on the small keyboard instrument, a physharmonica, that she is bringing along. Many child prodigies, so-called wunderkinder, are on the concert circuit in those days but the public is tired of seeing dolled-up children perform drills and as a consequence Clara’s receipts are smaller than the Wiecks have hoped for, the expenses greater than expected. |

|

1832 |

They finally reach Paris in February. Firstly, Clara has to present herself, demonstrate her talent and her virtuosity. In this she succeeds readily, even if she has only rickety pianos at her disposal for most of these private presentations that she has to give for free. Her first true concert is on April 9. The piano manufacturer Sébastien Érard lets her use one of his grand pianos, finally a good instrument but a bit hard in the attack. The Wiecks can be happy with the success although Clara plays only before a small audience: Paris is in the throes of a bad cholera epidemic and the public fears infection. Clara Wieck is now a celebrity in Paris. She makes important contacts: Giacomo Meyerbeer is much taken with her, in particular also Friedrich Kalkbrenner, the rich and influential composer and educator. Frédéric Chopin is rather reserved although he recognizes her as a great artist. Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy is enthusiastic and shall remain her friend forever. A kind of friendship develops with Franz Liszt although neither Clara nor her father can stand his theatrics that produce busted piano strings or do more serious damage still to the instruments he plays. In all the exertions of this concert tour, Clara still finds the time to write her nine witty Caprices en forme de Valse pour le Piano [op. 2]. The Wiecks return to Leipzig in April.

|

|

1833 |

Clara picks up scarlet fever but recovers fast and resumes her concert tours. The old Wieck devotes himself from now on exclusively to his daughter’s career and closes his music store. In these first years, she performs predominantly in Northern Germany and presents on average fifteen concerts in a season. Clara Wieck and Robert Schumann exchange romantic letters, innocent and flirtatious, that possibly remain hidden from her father but not from stepmother Clementine. Perhaps her new friend Emilie List knows of the love affair; she is the daughter of a high U.S. government official permanently assigned to Leipzig, a bit older than Clara, and she teaches her English. The ring finger of Robert’s right hand has become stiff and prevents him from playing the piano in public. The cause is very probably the persistent piano practice with the chiroplast, an apparatus that was recommended by Friedrich Wieck and holds the hands in what is considered their ideal position at the keyboard. Fortunately, Robert sees his life rather as a composer and can count on a few nice achievements already: his op. 1, the Abegg Variations, op. 2, the Papillons, and op. 3, the Caprices have appeared in print. He does no longer reside in Wieck’s house. |

|

1834 |

Clara is traveling again, plays in Magdeburg and Hannover (Hanover) among other places. Her biographer Dieter Kühn (see reference below) describes with which difficulties and hardships she and her father have to cope. They now often have a grand piano transported to the next venue (sometimes Wieck succeeds in selling the instrument right after the performance to an impressed listener); they have handbills printed and have a hired hand distribute them from door to door. Clara is everywhere a raving success but works for it dearly. Robert has just founded the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik whose first number appears in April. |

|

1835 |

This is an eventful year. Robert Schumann falls in love with one of Friedrich Wieck’s students, Ernestine von Fricken, and they even become engaged. Clara is heartbroken as she confides to Emilie List. Late in summer, Schumann breaks the engagement again. One November evening before leaving on another trip, Clara and Robert kiss for the first time in an unguarded moment, then again in Zwickau (near Dresden), before her first performance. Friedrich Wieck cannot help noticing that his 16-year old daughter and the student of his whom he does not hold in particularly high esteem, 25-years old, are making eyes at each other. As a consequence, his control over Clara becomes even stricter and, for the times he is not there, he plans every moment for her and her maid. |

|

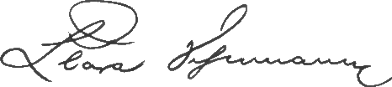

Clara Wieck at age 16 |

||

|

On November 9, Clara plays her Erstes Klavierkonzert [op. 7] under the direction of Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy for the first time, in the Gewandhaus in Leipzig. The public is friendly but the reception of her work is rather lukewarm. Later, the revised version of the Concerto will have great success. |

||

1836 |

In spite of her father’s constant control, Clara and Robert find together on the sly from time to time, principally in January when she is on a concert tour in Dresden. Friedrich finds out from the newspaper that Robert is in town. The choleric old man would hate to lose his daughter (and his source of income with her) to the unreliable tunesmith and he threatens to shoot Robert is he should dare to come close to Clara. Robert Schumann’s beloved mother dies on February 4. In April, Clara gives six concerts in Wroclaw (Breslau), each of them with a different program. She prefers works by Mendelssohn, Beethoven, Chopin, Schubert and Bach in this early phase of her career. Nothing of the big family conflict comes through. Frédéric Chopin visits Leipzig in September. Clara plays for him two of her works, the Quatre pièces caracéristiques [op. 5] and the Soirées musicales [op. 6]. He is in bad health but praises her compositions enthusiastically. |

|

1837 |

Start of another concert tour, this time through Northern Germany, in February. Clara and Friedrich Wieck pay a visit to her mother Marianne soon after arriving in Berlin. She is not doing well. Her husband Adolph Bargiel is ill and needs permanent care, probably after an apoplectic stroke. Her financial situation is bad as well; there is no indication that her daughter helps her out with money and this would also be hardly possible as Clara gets only a small allowance from her father now and then, from all that she is earning, just enough to pay for a cacao. As soon as they see each other again, Marianne and Friedrich start a heated quarrel, like in the years they were married. Clara receives a standing ovation at her soirée on February 25 with works by Bach, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Chopin and others; even her father is pleased with the performance. Six concerts in Berlin, then three in Hamburg, one in Bremen, all of them earning the greatest applause and netting a substantial income. She is now 18 years old and already a celebrity, a great artist, a diva. On August 13, Clara plays in Leipzig some of Robert Schumann’s Symphonische Etuden [op. 13] and they exchange engagement vows in writing on the 14th. Encouraged by his own professional success, Robert asks for Clara’s hand in a formal way, in a letter that she is to give Friedrich Wieck on September 13, her 19th birthday. Robert also musters the courage to talk to father Wieck in person and he writes her to have found nothing but ill will and, as expected, an icy rejection at this encounter. Another concert in Leipzig is on the agenda for October 8 and is immediately followed by the departure for Vienna via Prague. Clara’s biography reads like a list of stops on a concert tour, with the best of receptions everywhere. |

|

1838 |

The Wiecks stay in Vienna for four months and Clara celebrates one triumph after another. Her interpretation of Beethoven’s Sonata in F minor, his op. 2, is captivating, powerful, a bit faster than the public is used to hearing. Franz Grillparzer writes a poem about her performance, making fun of the critics. In all, she gives six concerts demonstrating her considerable repertoire: Beethoven’s Appassionata (his op. 57), her own Hexentanz [op. 5-1], works by Chopin, Mendelssohn, the Symphonische Etuden by Robert Schumann. |

|

Clara Wieck 1838 |

||

|

The Kaiser of Austria, Emperor Ferdinand I, invests Clara Wieck with the title of “Royal and Imperial Court Virtuosa”. She writes an Erinnerung an Wien ( = Souvenir of Vienna) [op. 9] using the theme of Haydn’s Kaiserhymne. Clara and Robert are still writing their love notes in secret. Father Wieck’s controlling and dominating behavior reaches intolerable degrees. |

||

1839 |

Friedrich Wieck writes his wife that he does not wish to see his sons Alwin, 16-years old, and Gustav, 15, any more as long as they have not become “respectable” individuals. Clara leaves alone on a concert tour, that is without her father but, after all, in the company of a French woman he hired and whom she does not like. She now has to arrange for everything herself and goes at it with drive and verve, the qualities she shows at the piano. Performances in Nürnberg (Nurnburg), Ansbach, Stuttgart (Stuttgardt) and Karlsruhe (Carlsruhe) are resounding successes. Finally Paris! The father sends her letters full of reproach, psychological pressure she does not need. However, she is supported by many friends and new acquaintances, for instance by Emilie List and the piano manufacturer Érard who puts his (a bit sluggish) grand pianos at her disposal, in the hotel and in the concert hall. Paris is at her feet. Her concerts and soirées are triumphs. Clara moves with her new travel companion and piano student Henriette Reichmann and with her friend Emilie List to Bougival, a suburb of Paris that can already be reached by train. She appreciates the peace and quiet and also saves some money this way. Robert does not answer her pleas to move in with them. She attempts to come to a reconciliation with her father; when Robert asks her to seek, if need be, court approval for their marriage plans, she begs him to forget the idea in order not to hurt the father’s feelings. But Robert has lost his patience. On June 15, he deposits an application with the District Court in Leipzig seeking the law’s official marriage consent. Friedrich Wieck is, of course, notified of the petition. Clara leaves Paris in mid-August. She attends a reconciliation session arranged by the Court in whose minutes solely Robert Schumann’s arguments are recorded as Friedrich Wieck does not show up. Before Clara leaves for Berlin to stay with her mother Marianne Bargiel, she goes to her father’s house in order to fetch (perhaps a pretense?) a coat of hers. The father instructs the maid to say that he does not know a Mademoiselle Wieck and not to let her into the house. In October, the three parties meet at a court-ordered session. Friedrich Wieck states a few conditions that could possibly bring him, he says, to drop his objections to Clara’s and Robert’s marriage. All the points he gives have to do with money and Clara’s obligations to him, ugly and hurtful. She is now persuaded also that the Court has to intervene. Clara and Robert celebrate Christmas at her mother’s house. |

|

1840 |

Robert Schumann writes more than 100 Lieder (songs) in the course of this year. He is now widely appreciated as a composer and has become well-to-do with a secure income. In February, the University of Jena gives him an honorary doctorate. On August 1, the Court accepts Robert Schumann’s petition and grants Clara and Robert the right to become married. The ceremony is to take place as soon as possible but Clara gives a few more concerts under her maiden name before the important date: in Jena, then in Gotha, the last one in Weimar before the Empress of Russia and her entourage. Following the habitual public announcement during four weeks, the wedding is celebrated on September 12 in the Nicolai-Kirche in Leipzig, on the day before Clara’s 21st birthday. |

|

1841 |

Scenes of marital bliss in the new lodgings in Leipzig, with new tasks and responsibilities for Clara. Rather detailed (at times embarrassing) information about the life as a couple gives the “marriage diary” that both, husband and spouse, keep current. The man of the house decides what to do. Clara must not play the piano when Robert is writing; he is at the time working on the first version of a symphony that shall be published later as op. 120. He is, in a sense, taking over the role of her father as a tutor, gives Clara lessons on the structure of the fugue, about counterpoint, on the way she should interpret the music she has in her repertoire. Invitations to perform are declined; the first presentation under her married name comes finally on March 31 in the Gewandhaus in Leipzig. Clara continues to write music; Robert is very much taken with her songs and has three of them [her op. 12] published together with his own as op. 37. Clara would like to have the grand piano from her father’s house. Friedrich Wieck finally gives in to her many requests but asks for an outrageous amount of money to have it transported the few blocks from the Grimmaische Gasse to her house in the Inselstrasse. On September 1st, Clara’s and Robert’s first child is born, daughter Marie. |

|

1842 |

Slowly and calmly, Clara Schumann starts again taking up her career as a concert pianist. She enjoys the work, sees it as her calling, but the young family also needs the income. She plays in Hamburg in January, Robert is coming with her. Then follows a painful separation and she journeys on to Copenhagen. Little Marie is in the care of relatives of hers. In Denmark, she makes the acquaintance of Hans Christian Andersen, the celebrated poet and author of fairy tales some of whose poems Robert has set to music. Andersen attends all three of her concerts and is thrilled by her as a person and an artist. |

|

1843 |

Clara’s father now lives in Dresden. He apparently should like to solve the conflict with his daughter and her husband, both now world-famous artists, and invites them for a talk. Their meeting in February is amicable, without harsh words. Clara’s and Robert’s second child, again a girl, is born on April 25 and is given the name Elise. Soon after giving birth, Clara resumes her studies and her practice routine with vigor. Fanny Hensel and her husband Wilhelm come to pay the Schumanns a visit. She is the sister of Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, twelve years older than Clara and is known as a brilliant concert pianist and composer as well. They have a long friendly conversation and do not show any rivalry. Unfortunately, Fannys talents and achievements are overshadowed by those of her famous brother. |

|

1844 |

In February, the Schumanns travel to Russia, a tour that is supposed to begin in St. Petersburg. A few concerts en route, two in the bitterly cold city of Königsberg (Konigsburg), three in Riga, then a trip through Lithuania in deep snow for a concert in Dorpat (about 300 km east of Riga). To the difficulties of this grueling itinerary have to be added the near daily presentations to attract concertgoers. In St. Petersburg, the Schumanns are passed from one salon to the next, Robert finds himself in the role as a kind of prince consort and is depressed. On March 3, a performance with works by Liszt, Chopin, Schumann, Mendelssohn, then three more concerts with a similar program in the few days following. An invitation to play for the Czar in the Winterpalace. Never ending applause at every appearance. And fabulous receipts! The biographer Dieter Kühn has calculated that Clara earned the equivalent of 100,000 € net. On toward Moscow; detour on miserable roads to see an old uncle of Robert’s who practices surgery in Tver. Robert is not feeling well, suffers from vertigo and claims to have moments in which he is totally blind. Clara takes care of business in Moscow all by herself and bathes in the glory of her success. Robert is slowly recuperating. For their return trip, the Schumanns board a ship in St. Petersburg that sails via Swinemunde to Szczecin (Stettin). In May, they are back home in Leipzig. Robert is still not feeling right, complains about horrible nightmares when he is able to sleep at all. He is disappointed not to have been invited to succeed Felix Mendelssohn as the Director of the Gewandhaus; his friend Felix has taken a leave of absence to travel through England and Italy, to rest and get new impressions for his work before possibly following the invitation of the King of Prussia to come to Berlin. The city of Dresden invites Robert to direct the choir; the Schumanns don’t lose much time to accept. They have a touching farewell party with friends and move on the 13th of December. |

|

1845 |

Julie, Clara’s and Robert’s third daughter is born on March 11. |

|

Clara Schumann with her daughter Marie, born 1840 |

||

|

Dresden society has apparently less interest in music than the Schumanns found in Leipzig. For sure, Richard Wagner has a very respected position as Director of music at Court but he is not a particularly warm friend of the family. Clara is glad to find again the celebrated soprano Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient. Another old friend is here also, fortunately, the Professor of surgery and obstetrics Carl Gustav Carus, personal physician of the King of Saxony. Robert’s frayed nerves trouble him and the family ever more often, but this affliction is interpreted as consequence of overexertion. Clara’s compositions op. [14], [15] and [16] are published by Breitkopf & Härtel in Leipzig. |

||

1846 |

Emil, the couple’s fourth child, the first son, is born on Febr. 8. Start on an extended concert tour in November, to bring them to Vienna, Brno (Brunn) and Prague. Robert and the two older girls are coming along, Julie and Emil stay in Dresden in the care of a nurse. This time Clara has only a moderate success in Vienna although her interpretation of Beethoven’s Concerto in G major is well received. She gives several concerts, also with Robert’s Piano concerto in A minor on the program, but the audience remains cool this time. During Clara’s last two performances in Vienna; Jenny Lind, the “Swedish Nightingale” and just about the same age as Clara, sings some of Robert’s Lieder, Clara plays Beethoven’s Appassionata to perfection, and the acclaim the artists receive is expressed in such a considerable amount of money that the entire trip is financed with it. |

|

1847 |

The Schumanns are back home only in early February and take off again a few weeks later, destination Berlin, to the premiere performance of Robert’s oratorio Das Paradies und die Peri, his op. 50. |

|

Clara and Robert Schumann, Vienna 1847 |

||

|

This turns out to be a horrible year: Fanny Hensel née Mendelssohn dies in May, only 41 years of age; Emil, the Schumanns’ little son born the year before, dies in July of a “glandular affliction”; the true friend Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy follows his sister Fanny and dies in November at the age of 38 years. |

||

1848 |

On the 20th of January, the Schumanns’ fifth child sees the world, the second boy, and is called Ludwig. A few evening performances by Clara with Wilhelmine Devrient. Life in Dresden is not particularly perturbed by the news of a revolution in Paris, wild demonstrations in Vienna and several German cities under the slogan of “Unity and Freedom”. Germany shall become a free country, no longer be a federation under the authority of princes. No chance to go on a concert tour in these troubled times. |

|

1849 |

When the May revolution erupts in Dresden, Clara is seven months pregnant. The revolutionaries are looking for Robert, they want him to participate in the skirmishes; Clara and Robert escape to a suburb, pick up the children on the following day. They all are granted refuge in Schloss Maxen, a castle about 8 km south of Dresden whose owner is a good friend; Robert, however, decides to return to the city. Clara and Robert have their sixth child on July 16, son Ferdinand. His godfather is Franz Schubert (not the composer), violinist at the Court orchestra in Dresden. |

|

1850 |

Ferdinand Hiller, Director of music of the city of Düsseldorf, gives notice to terminate his position with effect of April 1 because he wants to go to Cologne; he asks his valued colleague Robert Schumann if he were inclined to become his successor, he’d then put in a word for him. The salary is good, he says, 700 Thaler per year, but the city’s musicians are unruly and insubordinate. Robert asks the strange question if there is an asylum for the mentally ill in the vicinity of Düsseldorf as he had to be wary of “melancholic impressions”. Clara sees nothing but advantages in a move to this city. |

|

Clara and Robert Schumann, 1850 |

||

|

Clara and Robert take off on another concert tour that will take them to Leipzig, Hamburg and Bremen in February and March; shortly thereafter they take the decision to accept the position in Düsseldorf. In June is the premiere performance of Robert’s opera Genoveva, op. 81, in Leipzig; they stay on and Clara gives a series of performances in the course of July. On September 1, the dignitaries of Düsseldorf welcome the Schumann family cordially, with a brass band at the train station. The celebrations continue for nearly a week until Robert can finally start working with orchestra and choir. Robert conducts the first performance in his new position on October 24; Clara plays Mendelssohn’s Piano Concerto no. 1 and the applause for both is passionate. |

||

1851 |

Difficulties develop for Robert mainly with the choir. The singers “behave like school children” writes Clara, but she knows that her husband is not a good conductor and finds it hard to assert himself. They find an apartment with a large Salon in the splendid Königsallee, the luxurious central promenade, and they like it there very much. Much music is played, for friends and with friends. The hassle with choir and orchestra escalates. A new complaint: too many works by Robert Schumann are performed. The directorate tries to arbitrate, urgently, because the number of concert subscribers has diminished significantly. The seventh child of the Schumanns is born on the 1st of December, daughter Eugenie. |

|

1852 |

The old “nervous affliction”, principally acoustic hallucinations, bother Robert nearly the entire year. Even the strong Clara is going through hard times. She suffers a miscarriage shortly before her 33rd birthday. The Schumanns have to leave their lodgings but find a big suite in the Bilker Strasse. Members of the local music society demand of Robert in writing that he abandon his work as a conductor, in effect give up his position. |

|

1853 |

Clara is writing music again, Variationen über ein Thema Schumanns [op. 20], then Romanzen [22] and Lieder [23]. For the time after this year, P.-A. Koch, the author of her 1991 work index (see below), lists only another three compositions, and these without an opus number, namely Romanzen [WoO 29, from 1856], and Kadenzen to works by Beethoven [WoO 30, 1868?] and Mozart [WoO 31, year unknown]. In September, the young Johannes Brahms, just twenty years old, visits the Schumanns in Düsseldorf. He comes recommended by Joseph Joachim, their friend the violin virtuoso from Leipzig. Brahms plays his Piano Sonata in C major, op. 1, and lifts everybody’s spirits. “A genius” says an entry in Clara’s diary, “he has a higher calling” writes Robert in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. Johannes stays for four weeks, comes by every day to make music with Robert and Clara and for many visitors of theirs. Clara has taken up again playing in public, if only for small audiences. Robert terminates his contract as music director in November but the city is generous and pays his salary for another year. |

|

Friedrich Wieck, 1853, at age 68 |

||

1853 |

On a concert tour in Holland, to The Hague, Rotterdam, Amsterdam etc. Clara plays the beloved Appassionata by Beethoven plus many compositions by her husband to standing ovations for the both of them. They are back at home shortly before Christmas. |

|

1854 |

Robert’s “nervous afflictions” with vertigo, headaches and hallucinations of hearing have started already ten years before, but they now present themselves more often, appear worse and are lasting longer. Clara is pregnant again and her daily journal reports the anguish the family is suffering during this time. A friend speaks of Robert as a mentally ill person for the first time on February 20. On February 27, Carnival Monday, Robert Schumann leaves the apartment dressed only in a nightgown and in slippers without being noticed, walks through the city to about the middle of the pontoon bridge crossing the Rhein river, throws his wedding band into the water and plunges into the cold water himself. He is rescued by the bridge master and two courageous fishermen and then brought home. Robert’s suicide attempt comes possibly after a quarrel with Clara the night before who, as suspects her biographer Dieter Kühn, is to have told him that she could not stand this life any longer. Clara cannot see Robert in his miserable state and flees to stay with a lady friend of hers, without the children, but she follows the advice of the family physician in that, to both Robert’s and her own benefit. Brahms comes to Düsseldorf to help and support her as best he can. On March 4, Robert Schumann is admitted to the Institution for the treatment and care of the emotionally and mentally disturbed in Endenich near Bonn. Clara has not seen him again since he attempted to take his life. The house in Endenich is not a closed institution; the patients are living in an environment as calm as possible and corresponding approximately to the lifestyle to which they are used. However, Clara is not supposed to come see her husband in order to spare him the excitement. Consequently, nobody informs Robert of the birth of his son Felix on June 11 and he will not ever see him. Friends come often to Endenich and pay Robert a visit, for instance Johannes Brahms and Bettina von Arnim, Clara never. Nor does she go there to speak with the physicians, to inquire about Robert’s health. They start writing each other again in September. There exist no documents affirming that the relation of Johannes Brahms, the young and gifted composer, and Clara Schumann, the famous piano virtuoso 14 years his senior, went beyond romantic, lyrical affection; therefore, speculations of this kind ought to be dismissed, although he lives in her apartment and writes her longing letters. Clara plans and prepares new concert tours with intensity in order to come back into the milieu in which she feels secure and validated. She leaves in October, presents 22 concerts in total with many works by Robert, in Leipzig, Weimar, Hamburg and Berlin. The violinist Joseph Joachim, the baritone Julius Stockhausen and other famous artists contribute to several of her performances. |

|

1855 |

Clara Schumann is working incessantly. In January already she is on her way again, on a tour through Holland, then in April to Hamburg and Hannover (Hanover). Brief breaks only at home in Düsseldorf where she hopes, as she writes, to find a sign from Robert with the wish that she come see him. The physicians in Endenich report that Robert’s condition is deteriorating. Clara makes plans for the next concert tour nevertheless. Joseph Joachim and Johannes Brahms try to talk her out of this “ambitious chase”. Her financial situation (as estimated by the biographer Dieter Kühn) is very good indeed and thus appears what she calls her duty toward the family only as a pretext. A concert in Bad Ems near Koblenz in July, then an extended walking tour along the Rhein river with Johannes and her maid ending in Heidelberg. A few days in Düsseldorf, then she is off to Berlin again. Joachim, Brahms, the publisher Härtel and some of her prosperous friends want to pay her a kind of stipend of 700 to 800 Thaler per year, money that is supposed to keep her from traveling to England at least, a trip that is considered dangerous at the time. She does not respond to the offer. |

|

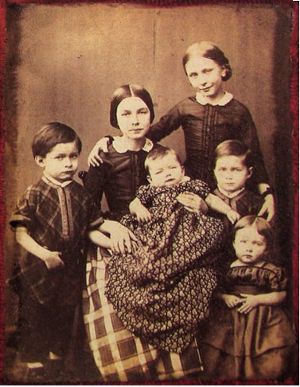

The children of the Schumanns in 1855 |

||

1856 |

Vienna, Prague, Pest (Pesh near Buda, Hungary) on her next concert tour in the spring. Again ovations following her interpretations of works by Schumann, Brahms and Beethoven. A brief pause in Düsseldorf, then the departure for London on April 8. She plays Mendelssohn, Weber, Schumann earning the enthusiastic applause that she has come to expect. A total of 26 performances giving a fabulous return! She is back in Düsseldorf in early July and meets, on the 14th, the owner and chief medical officer of the Endenich institution, Dr. Richarz, who tells her about Robert’s health. She goes to see Robert on July 27 for the first time since his attempt to commit suicide two-and-a-half years earlier. It is not certain that he recognizes her, he is no longer able to speak. Twice again she pays him a visit in the two days following. Robert Schumann dies alone on July 29, 1856, at 16h00. An autopsy is performed on the 30th by Drs. Richarz and Peters; the pathological findings are descriptive only and a definitive diagnosis of Schumann’s illness is not provided. All documents on his stay in Endenich and the postmortem examination existent to this date were critically evaluated recently by the specialist physicians Drs. Franz Hermann Franken and Uwe Henrik Peters, and the results published in 2006 (see reference below). The authors do not find any indication that Robert Schumann suffered from neurosyphilis; thus, such a suspicion has not been confirmed. Robert Schumann is buried on the evening of the 31st of July in the Old Cemetery in Bonn. Two weeks after Robert’s funeral, Clara and Johannes Brahms take a vacation trip through Southern Germany and Switzerland; the little sons Ludwig and Ferdinand as also Johannes’ sister Elise come along. In the course of this fateful year, the children are brought to live in various places: Ferdinand and Ludwig attend a boarding school near Jena; Marie and Elise live in a boarding house in Leipzig; Julie stays with her grandmother Bargiel in Berlin; only the two youngest children, Eugenie and Felix, live with their mother in Düsseldorf. Clara Schumann is back on the road in October, to give concerts in Denmark. She writes her last composition, the Romanze für Clavier in B minor [WoO 29]. |

|

1857 |

Concert tour through England, many others are to follow. The audiences are rather cool at first but will then receive her with enthusiasm. Works by Mendelssohn, in England particularly appreciated, then by Robert Schumann and by Beethoven are on the program, few of her own compositions. The receipts are in tune with the receptions: nothing less than excellent. |

|

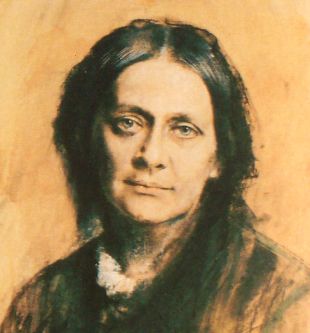

Clara Schumann at age 38 |

||

|

The Schumanns move to Berlin. In November, Clara complains about vicious rheumatic pain in the left arm, possibly a tendinitis, a consequence of too much work. At times, she has to carry the arm in a sling and takes opium as a pain killer. |

||

1858 |

She goes on a trip again, in spite of the pain in the arm, through Southern Germany with meager income, then through Switzerland. In total, she plays more than a dozen places. Johannes Brahms and Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient come to visit her in Berlin. The famous soprano has come back on the musical scene only shortly before, after having lived for years in seclusion because of a temporary failure of her voice. Clara fears that her own fate might be similar as she ages. She is driven: ever more concerts, in Cologne, Aix-la-Chapelle, Krefeld. The number of performances scheduled is so great that she can no longer plausibly invoke her financial responsibilities. Her personality becomes apparent in the way she behaves toward her children: she is tough, also severe, energetic, headstrong and self-centered, but not vain. |

|

1861 |

The cautious argument by Brahms that Clara is overdoing it with the concert work, is always answered in the same manner: apart from Ferdinand and Ludwig, the other five children also live with her now in the big apartment in Berlin, a lot of money goes out considering just the music lessons. This view is a bit one-sided because at least Marie, the oldest daughter, works without pause for her mother. In reality, Clara Schumann does not have to worry about the finances, and she must be aware of that in spite of her concerns. Brahms is impressed with her laments on this point and sends her at least once, and unsolicited, the sum of 200 Thaler, that is about 8,000 €. |

|

1862 |

Concerts in Paris: Clara Schumann plays the Conservatoire, then the Salon Érard with the baritone Julius Stockhausen and the singer/pianist Pauline Viardot. The playbill shows works by Robert Schumann, Schubert, Bach, Beethoven, Brahms; it is noticeable that she is rarely playing her own compositions in public. Clara buys a rather expensive little house on the outskirts of Baden-Baden (near Carlsruhe). |

|

1863 |

Voyage to Paris, financially not a success: “much honor, no money”. She moves from Berlin into her small house in Baden-Baden. Clara writes her daughter Elise about the flirtation with the composer Theodor Kirchner (born 1823) who resembles her deceased husband but is not quite up to him. |

|

1864 |

Concert tour to Russia with daughter Marie, St. Petersburg and Moscow, lasting from February to May. Clara gives 22 performances on about the same itinerary she traveled with her husband 20 years earlier. Robert Schumann’s works are now widely known in Russia and very much liked. The critics reproach her for playing too many popular, trite works and hardly any of her husband’s. She meets the distinguished piano virtuoso Anton Rubinstein (born 1829) who attends to her with loving care. The cultural life in Baden-Baden is interesting and Clara takes part in it with relish when she is home. Famous names all around her: Brahms, Turgenjew, Storm, Rubinstein, Viardot, Feuerbach and many others. |

|

1865 |

The fourth concert tour to England gets under way in May. A first performance in London’s Crystal Palace with Robert Schumann’s Concerto in A minor (his op. 54) has an audience of 4,000 visitors! Clara writes Brahms of the friendly public and how much Robert’s music is admired, but that, on the other hand, all idealism has to cede to business considerations. She plans to come regularly to England, every year, in order to be able to take care of her family in the proper style - the old tune. |

|

1867 |

London in the spring, with Joseph Joachim and his wife. Clara is feeling exceptionally well in spite of the fact that the receipts of her concerts are not too good this time. Ludwig Schumann, now 18 years old, is worrying Clara. He is unreliable in everything he undertakes, brooding and melancholic, and sometimes does not speak a word for an entire day. He soon gives up working as an apprentice at a bookseller’s. |

|

1869 |

This spring marks Clara Schumann’s seventh voyage (of a total of eighteen!) to England. Clara’s daughter Julie, a pretty young woman of 24 years, marries an Italian count. Johannes Brahms adored her from a distance since quite some time now. |

|

Julie Schumann, born 1845, at age 21 |

||

1870 |

Ferdinand Schumann has to serve as a soldier in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, comes back without injuries but addicted to morphine and Sulfonal, a particularly vicious hypnotic. He is not able to provide for his large family; Clara Schumann is saddled with this new problem and takes care of it in her way: the children are sent to live with relatives or as boarders and Clara pays for them. Julie, one of the granddaughters, lives with her from time to time. Son Ludwig is suffering from some form of paranoia and has become totally unresponsive. His subjective state and his demeanor have worsened to the point that Clara is obliged to have him committed in a private institution near Pirna. Given the scarcity of therapeutic options at the time, his condition is getting worse and so he is finally transferred to the notorious institution for incurable mental patients (the Landesheilanstalt für unheilbar Geisteskranke) in Colditz near Dresden. This is a true prison in which inhumane methods are used to subdue and tranquilize the inmates, as Ludwig’s brother Ferdinand and his sister Eugenie report with urgency. The diagnosis is schizophrenia. Ludwig’s mother does not come to see him in Colditz. |

|

1872 |

Daughter Julie dies at age 27 of tuberculosis, during her third pregnancy. Joseph Joachim would like to hire Clara Schumann as a teacher at his newly founded college of music in Berlin but she demands an outrageously high salary plus working conditions that he cannot accept. Clara’s mother Marianne Bargiel dies in March, 75 years of age, after a long illness. Clara Schumann is performing in London at the time. A circle of rich friends in Cologne make Clara an unusual present: they give her a parcel of stock certificates of the Rheinische Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft (the Rhenish Railroad Company) of a value of 30,000 Thaler; this amount alone would make her a wealthy woman. In addition, she is paid for her performances like a diva and does not even think of abandoning her hectic concert career or her highly remunerated piano lessons. Daughter Eugenie, 20 years old and an accomplished pianist in her own right, returns to help her sister Marie manage their mother’s household, arrange and carry out her concert trips. |

|

1873 |

Friedrich Wieck, Clara’s father, dies on October 6 at age 88, in Loschwitz near Dresden. In November, Clara, Marie and Eugenie move to Berlin, into a beautiful spacious apartment. The house in Baden-Baden will be sold later, at a loss. One week later Clara is already on the road again, on a concert tour through Northern Germany. She has to cut that short, though, after three concerts because of strong pains in the right forearm. |

|

1875 |

The recurrent debilitating pain forces Clara Schumann to interrupt her intense and exhausting concert activity. She is invited again to take a teaching position at the Berlin college of music, and she refuses again. |

|

1876 |

The pain in the arm has gone, at least from time to time, or it has become tolerable. Therefore: a trip to London in the spring, as usual, plus concerts on the continent on the way to, and on the return. Clara visits her son Ludwig for the first and only time in the Colditz asylum. He begs her to get him out of this prison. She replies that she can not help him. Another voyage at the beginning of the fall’s concert season. |

|

1877 |

Clara Schumann considers ever more often to leave the, for her, culturally sterile city of Berlin. She continues as before with her concert activity although the shoulder and the arms hurt badly. |

|

1878 |

Clara is offered a teaching position at the newly instituted Hochsche Conservatorium in Frankfurt/Main. The administration is very accommodating, grants her generous vacations, permits her to give piano lessons also in her own house and hires her daughters Marie and Eugenie as assistant piano teachers. She accepts although the salary of 2,000 Thaler annually is somewhat lower than what she expected; an important reason is the vicinity of the Taunus mountains. |

|

Clara Schumann at the age of 59 |

||

|

The family moves to Frankfurt in May, the new address is Myliusstrasse, close to the Palmengarten, an extended public garden with an ample collection of tropical plants. Clara’s youngest son Felix gives her much joy. He is handsome, musically gifted and wants to become a violinist but his mother talks him out of that early-on contending that this choice requires a particularly strong talent. So, he goes to Heidelberg to study jurisprudence. At the occasion of Clara Schumann’s 50th anniversary as a concert pianist, the Conservatorium honors her with a party and the city of Leipzig with a grandiose celebration in the course of which she is given a laurel wreath; she plays Robert’s piano concerto. |

||

1879 |

On February 18, Felix Schumann dies of tuberculosis as did his sister Julie six years earlier. Marie helps him in his last moments. His mother is just at that time giving a concert in the Städel Museum not far from the house. Clara Schumann and Franz Liszt play some four-handed pieces in a concert in Frankfurt but Clara finds the virtuoso’s theatrics disgusting. She starts work on a complete edition of Robert Schumann’s music. |

|

1880 |

Voyage to England in the spring. Clara is welcomed with open arms, gives eleven performances in London and earns a big pile of money. She is elected a member of the Royal Academy of Music. Then again concert trips through Southern Germany, Austria, the eastern parts of Germany. She is happy with her interpretation of Beeethoven’s Piano Concerto op. 73, his fifth, with the wonderful 3rd movement. She is inexhaustible, constantly on tour in this year and extraordinarily successful. For the first time (documented), she receives royalties for Robert Schumann’s works from the Peters Verlag; at that time, it is not usual for a publisher to share his profits with an author or a composer. |

|

1886 |

In the past years, Clara has become somewhat hard of hearing and is still complaining about the pain in arms and hands but she still likes to perform in public, praises herself to play “magnificently” and her memory is as good as ever. She is now working on the second part of the works of her late husband, the so-called Instruktive Ausgabe (i.e. the teaching edition). |

|

1887 |

The Complete Edition of Robert Schumann’s Works is published by Breitkopf und Härtel in Leipzig. |

|

Clara Schumann, 1888 |

||

1889 |

For her 70th birthday, Clara Schumann is awarded the Prussian Gold Medal for the Arts and Sciences by Kaiser Wilhelm II. Johannes Brahms has become a rich man as a composer and pianist and sends Clara a large amount of money, as he did twice before. He should like to contribute, with these 15,000 Mark, to pay for the expenses she has with her daughters and grandchildren. Clara mentions that she has put aside a nice capital but accepts gladly nevertheless. | |

1891 |

On March 12, Clara Schumann gives her farewell concert at the Conservatorium; this is her last public performance. She plays the Haydn-Variationen by Brahms, his op. 56b, the version for two pianos, together with a young colleague. Once again she earns long, rapturous applause. Daughter Eugenie leaves Frankfurt and moves to England. Clara’s and Robert’s son Ferdinand dies at the age of 41 years. The only son surviving is Ludwig who is buried alive in the Colditz institution. She continues giving piano lessons in the house but the greater part of this work is done by Marie. She also attends concerts in spite of the fact that she cannot hear the piano part through the sounds of the orchestra. A constant ringing in the ears, nowadays called tinnitus, plagues her. After suffering through a pneumonia in winter, Clara Schumann gives up teaching at the Conservatorium. |

|

1893 |

Clara Schumann now uses a wheelchair but carries on giving private piano lessons. |

|

Clara Schumann, 1894 |

||

1895 |

Johannes Brahms and Clara see each other for the last time in February; he plays for her the Piano Quartet in G minor, op. 25, with the melancholy Andante. |

|

1896 |

In March, Clara suffers a stroke, then a second one on May 10, this one more serious. She dies on May 20, at age 76. Marie, Eugenie and her grandson Ferdinand are with her. Brahms comes to Frankfurt in all haste from Bad Ischl in Austria, too late to see her but just in time for the funeral in the Old Cemetery in Bonn where she is laid to rest next to her husband. |

|

1897 |

Johannes Brahms dies on the 3rd of April, only ten months after his beloved Clara. |

|

|

Clara Schumann had to live through the death of four of her children: Emil (†1847), Julie (†1873), Felix (†1879) and Ferdinand (†1891). Her son Ludwig died at last 1899, still in the Colditz asylum. Her surviving daughters all saw the 20th century: Elise died in 1928, Marie 1929 and Eugenie in 1938.

|

||

Recommended literature |

||

|

|

Hermann Appel (Hg.): Robert Schumann in Endenich (1854-1856). Krankenakten, Briefzeugnisse und zeitgenössische Berichte. Schott, Mainz: 2006 (in German) Wolfgang Held: Clara und Robert Schumann. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt/Main: 2001 (in German) Paul-August Koch: Clara Wieck-Schumann. Kompositionen. Zimmermann, Frankfurt/Main: 1991 (in German) Dieter Kühn: Clara Schumann, Klavier. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt/Main: 1998 (in German) Susanna Reich: Clara Schumann. Piano Virtuoso. Clarion Books, New York: 1999 (in English) Monica Steegmann: Clara Schumann. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag. Reinbek: 2001 (in German) |

|

|

I wish to thank the ladies and gentlemen at the Schumann Haus in Zwickau/Germany for providing important information on the life and the work of Clara Wieck-Schumann.

|

||